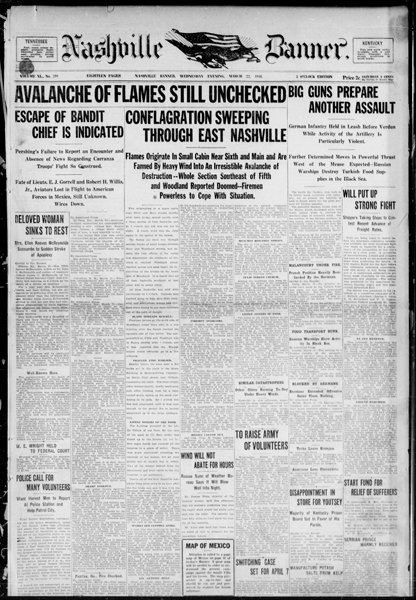

Fires in Tennessee

Engine Company No. 14 on Holly & 6th Streets,

Nashville, Tennessee, 1917

Library Photograph Collection

Fires have been a constant danger throughout Tennessee history, often resulting in significant damage to lives and property. In addition to numerous fires in Tennessee's vast forested areas, major fires in cities and towns — the Great Fire of 1878, the East Nashville Fire in 1916, the Old Hickory Powder Plant Fire in 1924, and the Chemical Plant Explosion in 1960 — have all left a mark on the state's history.

As Tennessee's population increased at the turn of the century, fires in urbanized areas had the potential to cause more damage, since the use of more flammable building materials and the relatively primitive resources of most fire departments made fires more difficult to control. In most communities, citizen-formed "bucket brigades" were the standard method of fire-fighting before the invention of the hand-pumped fire engines. In urban Nashville, the first volunteer fire-fighting unit was formed in May of 1807. In July of 1860 the Nashville Fire Department became an organized, paid department and employed its first steam fire engine, adding equipment such as hooks and ladders in 1862. It wasn't until 1912 that the first motorized fire engine went into service in the city. Even after the implementation of the finest equipment, the best training, and most advanced technology available, fires remain a danger in the dense urban areas, the sparsely-populated rural regions, and the heavily-forested regions of Tennessee.

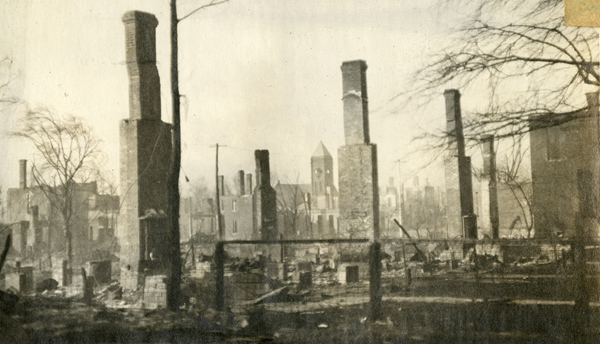

Panorama of East Nashville after the Great Fire, 1916

6th Street is on the left, Russell Street is in the middle, and Fatherland Street is on the far right.

Library Photograph Collection

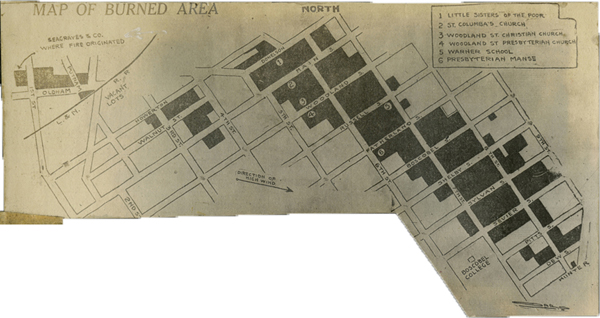

Great Fire, East Nashville, Tennessee, March 22, 1916

On the morning of Wednesday, March 22, 1916, a fire erupted in East Nashville, destroying over 500 houses and leaving over 2,500 people homeless. The fire originated at the home of Joe Jennings, who lived next to the Seagraves Planting Mill located on North First Street. Sparks from Jennings' home set the mill ablaze and from there the fire swept from 1st Street to Dew Street, consuming any homes and businesses in its path. Fortunately, there were few injuries and only one fatality, Johnson H. Woods, who was electrocuted by a live power line.

Unusually high winds gusting from 44-51 miles per hour across wooden-shingled roofs caused the fire to spread at a rapid pace, severely impeding the Nashville fire department's effort to control the blaze. Desperate to contain the fire, residents formed "bucket brigades" to help fight the flames, and many hastily removed furniture from their homes in an effort to save their belongings. Nashville Fire Chief Rozetta sent telegraphic messages appealing to every city within several hundred miles asking for engines and men to help combat the flames, and Governor Tom C. Rye mobilized the companies of the Tennessee National Guard in Nashville for guard duty and assistance with the rescue work.

Buildings belonging to the Little Sisters of the Poor Home for the Aged, Tulip Street Methodist Church, Woodland Street Presbyterian Church, Warner Public School, and Engine Company No. 5 were burned to the ground. All of East Nashville southeast of Fifth and Woodland Street was destroyed. Total property loss was estimated at more than 1.5 million dollars.

W. P. Barton Jr. Letter, 1916

Archives Manuscript Collection

Page 2 Page 3 Page 4

Little Sisters of the Poor, Nashville, Tennessee, March 1916 |

Warner School on 7th & Russell Streets, Nashville, Tennessee, March 1916 |

View from Tulip Street Church tower, Nashville, Tennessee, March 1916 |

Boscobel Street looking NW towards the Warner School, Nashville, Tennessee, March 1916 |

Rear of the Warner School from 7th & Fatherland Streets, Nashville, Tennessee, March 1916 |

7th Street looking towards Russell & 6th Streets, Nashville, Tennessee, March 1916 |

Woodland Street looking SW towards Tulip Street Church, Nashville, Tennessee, March 1916 |

Woodland & 6th Streets, Nashville, Tennessee, March 1916 |

6th & Russell Streets, Nashville, Tennessee, March 1916 |

View from Tulip Street Church tower looking NE down Russell Street, Nashville, Tennessee, March 1916 |

View from Tulip Street Church tower looking NW down 6th Street, Nashville, Tennessee, March 1916 |

Woodland Street Presbyterian Church, Nashville, Tennessee, March 1916 |

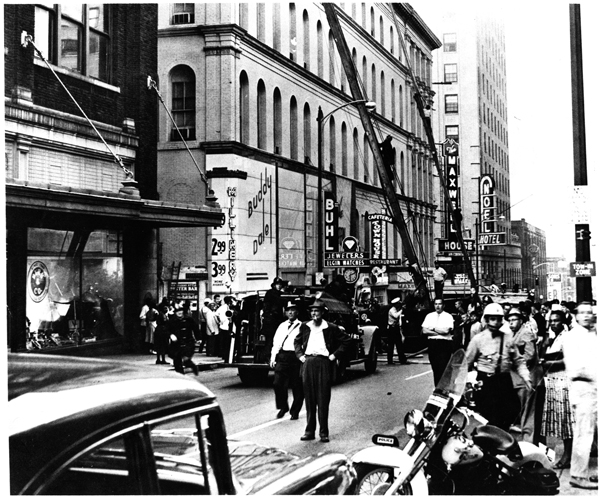

Maxwell House Hotel Fire, Nashville, Tennessee, December 25, 1961

Col. John Overton Jr. began construction on the Maxwell House Hotel in 1859. Named for his wife, Harriet Maxwell Overton, it was located on the northeast corner of Fourth Avenue North and Church Street in downtown Nashville. During the Civil War the occupying Union Army used the partially finished hotel as a barracks and prison hospital. Before the hotel was completed, the first national meeting of the Ku Klux Klan was held there in April of 1867.

Completed in 1869 at a cost of $500,000, the hotel had five stories and 240 rooms. The rooms cost $4 a day and the hotel advertised steam heat, gas lighting, and a bath on every floor. The hotel became famous for its Christmas dinners and boasted of boarding seven presidents, including Theodore Roosevelt, whose apocryphal comment that the coffee was "good to the last drop" became the slogan for Maxwell House Coffee.

On Christmas Night, 1961, the hotel caught fire and burned. The origin of the fire is unknown, but flames were first spotted on the 4th floor corridor. Within an hour the fire had spread to the 3rd and 5th floors and eventually through the roof. Between 60 and 70 people, both staff and guests, evacuated the hotel. The firemen on the scene eventually abandoned their efforts to save the hotel and instead attempted to prevent adjoining buildings from catching fire.

At the time, Fire Marshal Dan Hicks stated that the building was insured for one million dollars, and the acting hotel manager, Robert Witt, estimated that the damages to the furnishings were $100,000. J. W. Roach, chief city building inspector, stated the owners would most likely have to tear down what was left and rebuild. However, the Maxwell House was never rebuilt, and all that remains now of the once-famous hotel is an historical marker.

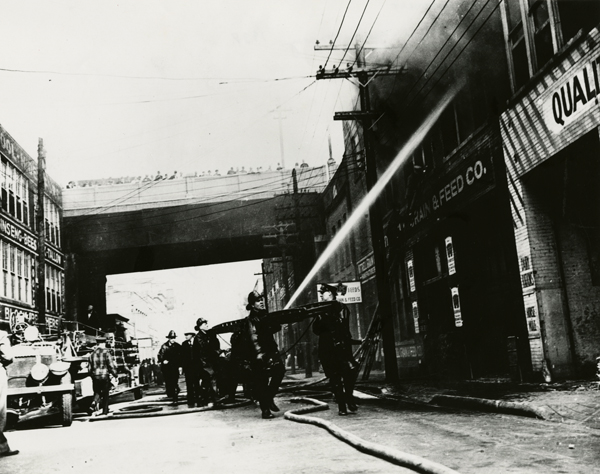

Firemen putting out a fire at 3rd Ave. Grain and Feed Company,

Nashville, Tennessee, 1938

Library Photograph Collection

Fairgrounds Fire, Nashville, Tennessee, September 20, 1965

At about 10:30 p.m. on September 20, 1965, a sudden fire broke out during opening night festivities at the Tennessee State Fairgrounds. Roaring out of control, it destroyed the 4-H Building, Women's Building, Merchantís Building, Administration Building, several restaurants, and the grandstand of the Racetrack. The Womenís and Merchantís Buildings housed art, antiques, crafts, and merchandise exhibits. Thankfully, no one was killed, but 18 were injured and property damage was estimated to be ten to twelve million dollars. The cause of the devastating fire is believed to be faulty wiring in the Womenís Building.

After the fire, the Grandstand was rebuilt. The other buildings were not reconstructed, and the current Creative Arts Building, Exhibitor's Building, Concessions Building, and Annex were built in their stead. Although the future of the fairgrounds is presently in doubt, the facilities are still used for conferences, expos, trade shows, the monthly Flea Market, and the annual Tennessee State Fair.

Three firemen fighting a fire at the Warner School, 626 Russell St.,

Nashville, Tennessee, ca. early 1940s

Library Photograph Collection

Maury County Jail Fire, Maury County, TN, June 26, 1977

On June 26, 1977, a fire in the Maury County Jail killed 42 people. The fire was started by Andy Zimmer, who had run away from a residential treatment center for emotionally disturbed teenagers in Dousman, Wisconsin. Police had picked up Zimmer earlier in the week on Interstate 65 for hitchhiking. While in custody at the Maury County Jail, he set fire to his padded cell, causing toxic gases and smoke to fill the jail through the ventilation system. Deputies were able to pull Zimmer from his cell, but other deputies, trying to free the rest of the jail's population, collided with panicked visitors and the only set of cell keys was knocked to the floor. It took several minutes to recover them, and by then most of the inmates had already succumbed to asphyxiation.

Overall, 42 people were killed: 34 inmates and 8 visitors. An additional 30 people suffered injuries. Zimmer was taken to Vanderbilt Hospital in Nashville with burns covering 25% of his body and was listed in critical condition. Facility inspectors had given the Maury County Jail a passing grade only the week before, citing that it met all necessary standards and ranking it 18th in a field of 102. However, the jail did not require a sprinkler system, nor was there an automatic cell lock system that could have been used to free all the inmates quickly; instead, each cell had to be individually unlocked, effectively trapping the jail's inhabitants in the fire.

The majority of the jail's inmates were not convicts; most were recent arrests still awaiting trial. In addition to inmates, visitors to the jail also became trapped during the panic that ensued after the fire began to spread. In one tragic case the Herman family, visiting a relative in jail awaiting trial, lost six family members.

Section researched and written by Kimberly Mills, Archival Assistant